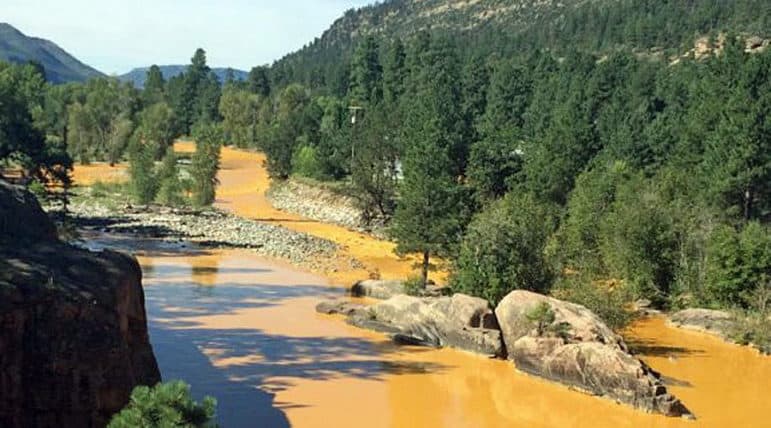

La Plata County / Courtesy photo

A scene from the Animas River in La Plata County, Colo., after the recent spill.

Farmers on the Navajo Nation continue to have problems in the wake of the recent spill of 3 million gallons of toxic waste into the Animas River.

The newest issue: Some in and around Shiprock, where water from the San Juan River still hasn’t been cleared for use, say a private company the EPA paid to deliver water brought contaminated liquid in used oil barrels.

“The barrels are not clean,” Farm Board Representative Joe Ben Jr. was quoted by KUNM radio in Albuquerque as saying. “They are from oil drilling operations.”

The toxic waste from the Gold King Mine in Southern Colorado, which sparked this disaster, flowed through the Animas into the San Juan last week and is making its way past the Navajo Nation. The EPA inadvertently triggered the spill at the mine.

“Disaster upon catastrophe” is how Shiprock Chapter President Duane “Chilli” Yazzie described on Facebook the EPA’s attempt to deliver water. As farmers “started to take water from the tanks for their corn and melons,” they noticed some of the water was “rust colored, smelled of petroleum and slick with oil.”

“The hopes of the farmers of actually being able to save some of the precious crops were obliterated in an instant with the tainted water. The farmers refused to use the water,” Yazzie wrote. “Crops are getting thirsty, it is reaching critical stage. Pray for rain.”

According to KUNM, “There are about 450 farmers in the Shiprock area, which is the agricultural hub of the Navajo Nation.”

The Farmington Daily Times wrote about a Monday meeting of the farmers:

Ben said he notified the EPA about the tanks and asked for certification that the tanks were in good condition to haul water. He said Monday that no one had responded to his requests.

During the emergency farmers meeting at the chapter house, Ben explained the situation to farmers and residents.

Sitting on a table were five plastic containers holding water samples — varying in color from yellow to brown — that Ben said were collected from the tanks.

Meanwhile, the Denver Post illustrated what’s at stake:

Roy Etcitty walked from his dead crops to the nearby banks of the San Juan River, where he stood in the mud and cried.

After more than a week without irrigating his field with the San Juan or using its waters to keep his horses hydrated, Etcitty, his long black hair waving in the evening breeze, pondered the river’s meaning and was overcome.

“It’s everything for us,” he said. “It’s a part of our life, they say. It’s our livelihood.”